Hermeneutics

Introduction: The Need for Hermeneutics

Let me begin with a true story. When I first went to Australia, a friend (male) who stayed there brought me around Sydney. When we arrived at a shopping mall, he asked, “Would you like to buy some thongs?”

I was shocked!

“Why on earth would I ever want to buy thongs?” I asked.

“Well, don’t you need it when you go to the beach?”

“What’s wrong with you? Why do I need to wear thongs to the beach?! I’m a guy for crying out loud!”

At that point, my friend realised that we both understood the word, “thongs”, very differently.

For most people in Singapore, “thongs” refer to bikinis.

But for the Australians, “thongs” refer to slippers.

Though we belong to the same era, the 21st century, we belong to two different cultures, and we thus have different conceptions and understandings of the same thing.

Hence, the importance of hermeneutics: the art of interpretation.

When it comes to interpretation (of art, literature, a speech, or a movie), it is necessary that we interpret the subject in the right context.

There is a tendency to take it for granted that people of different cultures and eras see the world the same way that we do. The issue of interpretation may not be a major issue in the past because culture back then did not change as rapidly as the culture of today.

As we have learnt from the earlier story, the same word has different meanings in different cultures. And so, what more can we expect if we were to attempt to interpret Chinese landscape art, which is not only from a different culture, but also from a different era?

The way we perceive and understand the various elements may differ. If we are interested in an authentic interpretation, if we are interested in knowing how the Chinese then understood the work of art, we will thus need to (figuratively) re-focus our lenses, so that we may be able to look at it with the same interpretive lens as the Chinese in that culture and era.

Taken out of context, we can still derive an interpretation. But what I hope to do, in addition to providing an interpretation, is to help you to appreciate Chinese landscape art the same way as the artists and lovers of art then, had appreciated it.

Cultural-Historical Points

What do we know about art in the Song (宋) Dynasty?

In that period, Taoist philosophy (not the same as the Taoist religion) greatly influenced art. It was the influence of Taoist philosophy that inspired many artists to paint nature rather than people.

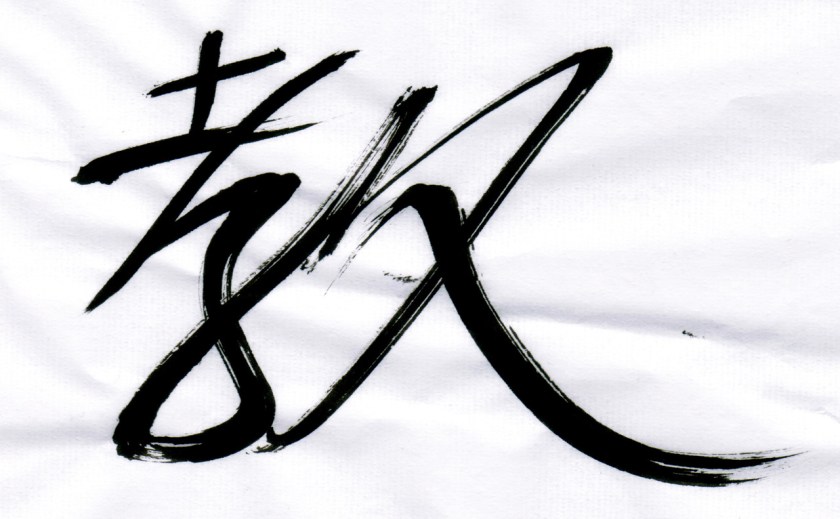

But what is the Tao (道)?

Take a look at this photograph. Is it beautiful?

Now, try to express that beauty in words. Are you able to do so?

In the words of the Chinese poet, T’ao Ch’ien (陶潛), when we are faced with the beauty of nature:

Yet when we would express it, words suddenly fail us.

此中有真意,欲辨已忘言。

T’ao Ch’ien (陶潛), Drinking Wine (飲酒)

From the Tao Te Ching (道德經), we are told:

The way that can be spoken of is not The Way. The name that can be named is not The Name.

道可道,非常道。名可名,非常名。

Lao Tzu (老子), Tao Te Ching (道德經), n.1

And elsewhere:

There was something formless yet complete that existed before heaven and earth, without sound, without substance, dependent on nothing, unchanging, all-pervading, unfailing. One may think of it as the mother of all things under heaven. Its true name I do not know. Tao is the by-name that I give it.

有物混成,先天地生。寂兮寥兮,獨立不改,周行而不殆,可以為天下母。吾不知其名,字之曰道。

Lao Tzu (老子), Tao Te Ching (道德經), n.25

When we come face to face with nature and its beauty, we experience something wonderful, something mystical. It’s a real experience, and yet, we are not able to properly define it. That is the Tao (道).

And it is this Tao (道) that was central in Chinese painting, especially in the Song (宋) Dynasty, and it affected the creative imagination, the creator and the created, the animate and the inanimate, the human and the non-human. It affected the subject matter and even its interpretation. So much so that in the Song (宋) Dynasty, the aim of the painter was to capture not just the outer appearance of a subject, but its inner essence as well – it’s energy, life, force, and spirit. In short, the painter tries to capture the Tao (道) in his artwork.

But why landscape art?

Back then, it was the view that the good man has a deep need to cultivate his mind, to nourish in himself his original nature in its simplicity. For someone who lives in the world, nature alone permits man to return to that oneness.

For many of us who live in the city, we can identify with that. Every day, we are faced with the non-stop hustle and bustle of activity. To just take a step back and take a stroll in a garden or forest, we find ourselves refreshed, renewed. What do we find when we are having that nice relaxing stroll in the park?

Peace. Serenity. Harmony.

Away from the city, Man finds himself in harmony with nature. No one is the master nor is any one the slave. Both Man and nature meet each other on equal terms. For the Chinese, real communion (oneness) can only exist between equals.

And so, the living representation of a landscape may give the mind the necessary means of escape, and provides one with a chance to commune with nature despite his inability to be there physically.

These principles are true for most painters in the Song (宋) Dynasty. From the writings of Kuo Hsi (郭熙), the painter of the art work we will be looking at today, we can be certain that he subscribes to all these as the foundational elements in his works.

Objective

I would like to focus mainly on the role of space and time in this painting. We live in the confines of space and time. Our thoughts are mostly structured in terms of space and time. When we look at art, we look at it in a particular space and in a particular moment in time.

I would like to focus mainly on the role of space and time in this painting. We live in the confines of space and time. Our thoughts are mostly structured in terms of space and time. When we look at art, we look at it in a particular space and in a particular moment in time.

But when it comes to paintings, people often think of space as being two-dimensional, though sometimes creating a feel of it being three-dimensional. And unless an art-work takes on the form of a narrative, the concept of time does not seem to apply.

And yet, in Chinese landscape art, the artist tries to situate the viewer within space and time.

With reference to this particular painting, I would like to show how Chinese landscape art tries to create a sense of traversing a three-dimensional space, while simultaneously embodying the movement of time in a non-narrative still image. After which, I hope to be your guide, and bring you through this beautiful landscape, and at the same time to experience the progression of space and time in a painting like this. I hope that in the process, you may also be able to commune with nature and come face to face with the Tao (道).

Formal Properties

This painting, entitled, “Snow in the Early Spring at Guanshan” (關山春雪圖), is painted on silk, measuring 197.1cm by 51.2cm.

Notice how there is a cliff at the bottom. Kuo Hsi (郭熙) painted it to give the viewer the illusion of standing at the edge of a cliff to admire the scenery before him. Keeping in mind that this painting is about two metres tall, Kuo Hsi (郭熙) invites us, the viewer, to first situate ourselves there and to admire the rest of the painting with him.

Look away and now, look back at the picture again. What is the first thing that captures your attention? It will be the sky. Kuo Hsi (郭熙) cleverly painted it to contrast it from the rest of the snow-covered mountains.

This would be the first thing in which we have been invited to look at and contemplate (默觀 moguan). Its Chinese meaning is very deep. 默 (mo) refers to being silent and still. 觀 (guan) refers to studying, observing, and at the same time, refers to looking with one’s eyes. These two words come together to form a beautiful understanding of contemplation: To contemplate is to be still and silently study and observe the Tao (道).

Let us return to the painting. The darkness of the sky sets the mood for us. On a cloudy day, or even at night, if one were to be by himself in such a setting, one naturally gets a sense of the serenity. There is no else but me, and I am as such, led into a contemplative mood.

Notice how Kuo Hsi (郭熙) first gives us a sense of vastness by darkening the sky, so as to contrast the snow-covered mountains. Had the sky been the same colour as the mountains, the immense ridges would not stand out, nor would we be able to perceive the dark area at the top, and the area of white at the bottom. This creates the impression that what is before us is an immense space of sky and mountains. Despite the thin narrow frame of the artwork, what is before us is a landscape both far and wide.

Having thus admired the sky, we lower our gaze down to the tall mountain peaks that decorate the distant space (backdrop) of the scenery before us.

Notice how these peaks have been painted with smooth brush strokes, with angles that are not so sharp. The tension-free strokes of Kuo Hsi (郭熙), creates a calming effect. In the early Spring, where the snow has not yet melted away, all is but calm. Life has not sprung into its full bloom, and so the activity of nature has not reached its peak.

Let us now lower our gaze just a little. Notice how in the region just above the trees and the peaks (in the distant space), and the region between the trees above the houses and the presiding hill behind it, there is what seems to be a white mist.

This technique is known as “atmospheric perspective”. It is a method Kuo Hsi (郭熙) used to create the illusion of space and distance by depicting objects in progressively lighter tone as they recede into the depths. These areas of mists obscure the top of trees and increase the sense of height by masking the bases of these cliffs. Look very carefully at the painting and you would notice that the bases of the hills are absent. As such, we are left to imagine just how high up in the heavens we are, as we picture ourselves moving around in the landscape.

Let us lower our gaze once more, now focusing on the presiding hill that is crowned with the lush vegetation on its top, and just in front of it at the bottom, a hut, designed rather simplistically. Notice how the simplicity of the hut contrasts with the complexity of the lush vegetation that surrounds it, both around and above. And below the hut, we find a stream of water flowing down a small waterfall, into the murmuring river.

Notice how all these “activity” converges around the hut. Notice how this activity adds life to the still serenity of the entire painting. And notice how the hut contrasts with its surroundings by displaying a kind of stillness. This stillness dissipates the surrounding tension. Even in the midst of the serenity and activity of nature, Man is still quite capable of achieving that contemplative serenity within him. He remains a person unperturbed by his surrounding.

This hut is the only presence of human activity in the painting. This is significant on several levels. Human activity is depicted to draw the viewer to a new awareness of the relationship which one has with nature.

But what is this new awareness of the relationship about?

Just as how we find trees and rocks in nature, the hut is made up of trees and rocks (soil included). Earlier I spoke about how Man seeks communion with nature. Here, we see the hut surrounded by nature and its activity, and yet the hut does not stand out like a sore thumb. Here we see that Man is one with nature. Man complements nature, and is in turn, complemented by nature.

The Symbolic Meaning

So far, I have said very little about space and almost nothing about time. How then do these elements come into play?

As I had mentioned earlier, the purpose of Chinese landscape art is to invite the viewer to roam around freely in the landscape as a way of experiencing and communing with nature.

Let us begin traversing the painting.

As I mentioned earlier, when we first stand before this beautiful work of art, it is as if we are standing at the edge of a cliff, admiring the view before us. We begin our gaze of admiration from the top and move downwards, slowly, admiring every fine detail before us as a lover of nature would.

When our eyes have reached the hut, we re-position ourselves as if we are standing in the hut, peering out of the window to admire the vast scenery before us. Here and now, we are in the heart of nature, communing with nature as the elements converge into the middle space in which the hut occupies.

Eventually, we find a little walkway on the hill, towards the right, inviting us to leave the house and walk through that path. And so we walk. Notice that as you ascend that little hill, your gaze begins to rise higher and higher.

And so, slowly yet steadily, you ascend the path up the hill. And finally, you have reached the top of the presiding hill, on a sort of plateau, surrounded now by the lush greenery around you. And again, you pause to walk around and soak in the atmosphere, to soak in the beautiful scenery that stands before you, of the trees, of the mists separating you from the mountain peaks, and of the snow-covered mountain peaks.

No one else is with you. You are alone, but yet, you are not alone. Nature surrounds you and is your company and friend.

Now, look up. Admire those tall peaks that stand so solemnly as if deep in thought. Join them in their contemplation of nature. Raise your head a little higher now, and admire the rich blue sky. Peer into the heavens and, like a bird, let your gaze and your thoughts sore through the sky.

When you are done, you may now begin your slow descend of the hills and return back to the hut, and eventually back to the world.

Notice how, as I guided you through the landscape, you have experienced a sense of space and time?

Though the art work is still, notice how we have nonetheless moved through space by moving in and out, up and down the various portions of the landscape. Notice how we have also moved through time. Even though the painting is a still image, its individual parts come alive as we move through it, as if we were watching a video documentary of Guanshan Mountains. Or, better still, it is as if we had actually been there, walking in the midst of it, admiring its beautiful scenery, and communing with nature.

If you have tried your best to follow me on that journey, are you left in wonder? Are you amazed at its beauty? If so, are you able to express that beauty and wonder in words? Or does it fail you?

If words are not sufficient to express what you have experienced, you have come face to face with the Tao (道).

References

Fung Yu-Lan, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy (New York: Free Press, 1948), pp.16-29

George Rowley, Principles of Chinese Painting (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1959), 2nd ed, pp.3-22

James Cahill, Chinese Painting (New York: Rizzoli, 1985), pp.2-63

Nicole Vandier-Nicolas, Chinese Painting: An Expression of a Civilisation (New York: Rizzoli, 1983), Translated by Janet Seligman, pp.99-108.

“宋郭熙关山春雪图”, 百度百科, accessed 7 September 2010, http://baike.baidu.com/view/621756.htm

I would like to focus mainly on the role of space and time in this painting. We live in the confines of space and time. Our thoughts are mostly structured in terms of space and time. When we look at art, we look at it in a particular space and in a particular moment in time.

I would like to focus mainly on the role of space and time in this painting. We live in the confines of space and time. Our thoughts are mostly structured in terms of space and time. When we look at art, we look at it in a particular space and in a particular moment in time.